Is there a role for apology in U.S. foreign relations?

Posted by John Dickson in International, Public Affairs on January 21, 2016

The apology that a U.S. sailor gave after being detained by Iranian security forces in Iranian waters has set off a firestorm of criticism over the humiliation of our military. The video that was taken by Iranian soldiers saw the man identified as the commander of the U.S. vessel as saying, “It was a mistake that was our fault and we apologize for our mistake. It was a misunderstanding. We did not mean to go into Iranian territorial water. The Iranian behavior was fantastic while we were here. We thank you very much for your hospitality and your assistance.”

Cries of a “disgrace” and “humiliating” were heard by those who could not bring themselves to credit the diplomats with the sailors’ release and the avoidance of an international incident that could have derailed not only the nuclear deal with Iran, but also, we have since learned, an exchange of prisoners that had been the subject of negotiations for well over a year. One Congressman, Tom Rooney, from Florida and a member of the House Select Permanent Intelligence Committee, implied that the State Department had instructed the sailors to “make that kind of statement.” The State Department was vigorous in its denial that an apology had been issued in order to obtain the release of the sailors.

Absent from the back and forth of accusation and denial is any discussion of the merits of apology, either as national policy or behavior, towards foreign or domestic parties.

The rush to reject apology makes one wonder what happens to the approach to family disputes. Is an apology under those circumstances a sign of weakness, or is it a recognition that the path towards resolution might require an apology?

For sure, foreign policy is not marital reconciliation. Yet, history shows apologies have been an element of U.S. behavior, at home and abroad.

Coincidentally, the sailor’s apology came within days of the anniversary of the U.S. overthrow of the legitimate ruling monarchy of Hawaii. On the 100th anniversary of that event, a bipartisan majority in Congress issued a resolution apologizing to “to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893” and for the “deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.”

Other examples spring readily to mind: the issuance of apology to and even compensation paid to the Japanese-Americans sent to detention camps during World War II (an event that Donald Trump cited as justification to ban the entry of all Muslims into the U.S.)

Less well known was the first visit to Mexico by a sitting U.S. President, Harry Truman, in 1947. Truman did not have to utter the precise words of apology as he laid a wreath at the Mexican monument to their Niños Héroes on the eve of the centennial of the war with Mexico which saw the loss of nearly half of its territory. Mexicans not only took the gesture as an apology, but, instead of seeing it as weakness, they received it in the way it was offered. They enthusiastically embraced Truman as a “new champion of American solidarity and understanding,” in the words of Mexican Foreign Minister Ramon Beteta. Others went further, as one eyewitness was quoted as saying, “one hundred years of misunderstanding and bitterness wiped out by one man in one minute.” The response led President Clinton to repeat the gesture in 1997 when he visited Mexico City.

U.S. allies around the world are less reluctant to abjure apology as a component in their foreign relations. In 2007, the British government expressed regret and authorized payments of £20 million to compensate victims tortured by its forces during the Mau Mau rebellion against British rule in Kenya in the 1950s. Just last month, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offered “apologies and remorse” for the “immeasurable and painful experiences” suffered by women in Korea forced to provide sexual services to Japanese soldiers during the World War II. As part of a settlement with the government of South Korea, Japan agreed to make payments to a fund for victims. Other examples include Canada’s apology in 2008 to First Nations peoples for the system of Indian Residential Schools and Australia’s apology in 2014 to Indonesia for naval ships straying into Indonesian waters without permission.

The apology last week in the Persian Gulf differed from other examples in that it was likely a spur-of-the-moment decision by the commander, as opposed to national policy arrived at after considerable discussion, and in the Hawaii and Mexico examples, after 100 years has lapsed. More recently, though, we have the cases of the U.S. and NATO forces who apologized for military operations in Afghanistan that result in civilian deaths.

Presidential politics make the issue of apology harder. Taking a cue from Mitt Romney’s 2010 campaign book titled, No Apology: The Case for American Greatness, candidates and pundits on the eve of the Iowa caucuses rushed to criticize weakness, claiming as well that the Iranians violated the Geneva Convention and its clauses related to treatment of prisoners in wartime. Such short memories. Less than ten years ago, these same individuals were trying to back away from and even rewrite that convention to suit U.S. methods of interrogation.

A refusal to accept any measure of accountability for U.S. behavior implies that no actions have been taken that have been either mistaken or misguided or immoral. Or that they were justified to make America great.

In discussing the negotiations that Secretary Kerry and his team had with Iran over the prisoner exchange, he recalled that the Iranians repeatedly raised the 1953 coup organized by U.S. intelligence to overthrow the legitimately elected Mohammad Mossadegh as President of Iran. The Iranians remember, and we deny.

I do subscribe to the notion of greatness for my country that I served for almost 30 years. It is a greatness, though, that has the strength, confidence and wisdom to hold itself accountable for its errors and to aspire to do better.

This post originally appeared on History News Network.

Present at the Creation – The Stone Marker at Pontoosuc Lake

Posted by John Dickson in Berkshires, History in our surroundings, Personal memory, Preservation on January 11, 2016

The stone marker lies face up just inside the chain link fence near the dam at the outlet of Pontoosuc Lake, the headwaters of the west branch of the Housatonic River. There on the ground, it’s easily missed for the exercise conscious and soul refreshers who pass by on their way to the lake, the ancient stand of pines and their commanding view up the valley to Mt. Greylock. Now with a layer of snow and frozen ice, it’s impossible to read the inscription underneath: “The top of the iron pin is 50 inches above the old dam.”

Of course, no iron pin is in sight, since this marker is dated November 1, 1866, a year after the Civil War ended. Another date is on the green bridge railing, speaking to an upgrade that took place in 1994, shoring up the dam, adding new barriers and stone lining to the canal and redirecting its water back to the river in order to prevent further erosion on the hillside.

The 1866 marker points us back to an “old dam,” fifty inches lower. Perhaps there are other stones somewhere still to be found that indicate the 1866 dam was itself raised in 1824, 6 feet higher than the original dam, built in 1763.

More than 250 years have passed since the original construction of this dam that harnessed the falling waters of the Housatonic to power the industry that drew jobs and people to the city and the region.

Imagine what Pittsfield in 1762 looked like to Joseph Keeler who, approaching the age of 50, uprooted his family of ten from Ridgefield, Connecticut to settle here. Perhaps what drew him here was the news of Pittsfield’s incorporation just one year earlier in 1761 and the promise of jobs and wealth for his coming of age sons. He settled first in present day Lanesboro, and, after a year of checking out the region, he saw his opportunity on the south shore of the large lake just across the town border. He might have called it Lanesboro Pond, or the unwieldy Shoonkeekmoonkeek, but not Pontoosuc yet, since that was what the whole settlement had been called prior to incorporation.

Keeler purchased over 200 acres from one of the town’s original settlers, Col. William Williams. His new plot ranged from the southernmost tip of the lake extending over 100 yards further south. There, in 1763, Keeler and his sons built the first dam, in order to power two mills he also constructed, a grist mill for grinding flour and a saw mill.

In one respect, it was an ideal spot since his neighbor, Hosea Merrill ran a lumber operation taking advantage of the abundance of tall white pines, still in evidence in the area. On the other hand, it was far from ideal, since there was no road between the center of the new town and this outpost. It took four more years for another entrepreneur, Charles Goodrich, to build that road, only to receive the news that the town refused to reimburse him for the cost. Goodrich had started an iron forge downstream, perhaps taking advantage of the swiftly moving water from Keeler’s dam to fuel the bellows for heating the coal fires at the forge. He would also have needed the water as a supply to cool down the newly shaped iron pieces of saws and scythes, axes and axles for wagon wheels and other assorted metal work.

From these origins, from this dam, Keeler’s mills and Goodrich’s iron forge spawned the early industry of the town. As ownership passed from these two men on to others, the advantages of the upper reaches of the Housatonic attracted still more enterprising and innovative men.

Goodrich’s forge eventually became a gun shop that was sold in 1808 to another recent arrival from a Southampton Massachusetts blacksmith family, Lemuel Pomeroy. Securing a government contract, Pomeroy expanded his business to produce 2000 muskets a year until 1846. His business acumen was not limited to guns, however, as Pomeroy built one of the town’s first textile mills, on the site of yet another grist mill southwest of the town center. When Pomeroy stopped selling guns, his factory was converted into one of the largest woolen mills in Pittsfield, the Taconic Mills, whose complex stood at the corner of Wahconah and North Streets.

The Keelers had unloaded their properties by 1813, selling off parcels, including one to James Strandring who set up a tool-making factory about 300 yards south of the dam. His manufacture of comb-plates and spindles for carding and spinning wool drew the inventor Arthur Schofield to set up shop in his attic. Schofield had brought to Pittsfield the makings of a carding machine that would transform the production of wool from a hand-spun, cottage industry to the heavy industrial output from the massive brick factories that dominated Pittsfield’s landscape over the next 150 years – all powered for many years by, you guessed it, water.

The first upgrade to Keeler’s dam accommodated a group of investors who bought the site and Strandring’s small factory and, half-way between the two, they started the Pontoosuc Woolen Mill in 1826. This mill outlasted the ten other woolen mills in the town, which before the Civil War helped make Berkshire County the largest producer of woolen cloth in the nation, and helped attract to the region the thousands of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Quebec, Poland and elsewhere who make up so much of our population.

The second upgrade came as our stone marker suggests in 1866, at the end of the Civil War, when factories sought to ramp up their production with the new peace dividend. And the last upgrade was actually a downgrade that came in 1994, 21 years after the last woolen mill, Pontoosuc, then named Wyandotte, closed down.

It’s a simple inscription on this stone marker, that hardly anyone sees. But it tells a story, our story.

This also appeared in the Berkshire Eagle.

Melville Helps Us Understand Trump

Posted by John Dickson in Berkshires, Immigration, Public Affairs, Public History on December 9, 2015

Perhaps it is time to reconsider Herman Melville, not for the whale, but for his social commentary that speaks to us across generations in this Presidential campaign season. Melville will return to the news in the next few weeks following the release of the much promoted Ron Howard movie “In the Heart of the Sea,” the account of the sinking of the whaling ship Essex that inspired Moby Dick. As Americans, we grow up knowing the broad parameters of Melville’s tale (not tail), even if we never made it past the first chapter. Ahab’s chasing the white whale is part of our cultural DNA, shorthand for an obsessive, disastrous pursuit.

Embedded into this novel, written in Pittsfield shortly after Melville moved here in 1850, though, is the story of Ishmael, the sailor-narrator, and Queequeg, the tattooed, heathen Polynesian harpooner who was peddling shrunken heads when Ishmael first met him. The novel begins with the two sharing a room (and, as was routine in the early 1800s for men of little means, a bed.) Initially terrified of Queequeg, Ishmael concludes that “The man’s a human being just as I am: he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him.” Melville’s summation reaches across 175 years with a pointed rebuke of politics following the San Bernadino shooting after Thanksgiving: “Ignorance is the parent of fear.”

As Melville was writing these lines, he was surrounded by an outburst of nativism, of anti-foreign and anti-Catholic sentiment in Massachusetts, where a new, secret society was gaining adherents: the Know-Nothings. That anti-party political order bequeathed the nation one of the most colorful but also confounding names, opening up the obvious line of inquiry – who would want to be associated with a movement that embraces ignorance in its title?

Citizen Know Nothing

The Know Nothing name emerged not from a desire to be equated with stupidity, but from the secretive nature of its early days when adherents were instructed to answer questions about the order by saying they “know nothing.” Following their success in several state political elections in 1854, they gave themselves the respectable official title, the American Party, but the Know Nothing name given to them by outsiders had already stuck.

In 2015, the current crop of Republican Presidential candidates seems to drawing for their playbooks a page from the 1850s and the Know Nothings. They are drawing on several themes and tactics from the 19th century movement, most notably anti-immigration and the rejection of traditional politics. The third pillar of the Know Nothings, anti-Catholicism, could easily be updated using the “replace all” function on a computer, substituting in the word Muslim for the earlier threat to Protestant values.

One Know Nothing member, Henry Wilson, who was elected as a U.S. senator from Massachusetts, relayed the 1850s playbook, describing the secret order whose “professed purpose was to check foreign influence, purify the ballot box and rebuke the effort to exclude the Bible from the public schools.” The societies that fed into the political movement bore their anti-immigrant leanings in their names: Sons of America, the American Protestant Association, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, and the Order of United Americans. Members took oaths, according to a national convention in November 1854, to “not vote for any man for any office…unless he be an American-born citizen.” If elected or appointed to any office, the member would “remove all foreigners, aliens of Roman Catholics from office or place.”

The nativism of the Know Nothings crept over into an overarching contempt for politicians, in reaction to a perceived increase of immigrants and Catholics in politics. The movement then saw its greatest growth spurt in a period of generalized dissatisfaction with the inability of both parties to deal with the major issues of the time. Failure of the Whigs in the Presidential elections of 1854 and the only temporary resolution of the slavery issue in 1850 left a vacuum in the two-party system, leading quickly to the disappearance of the Whig party . New issues such as temperance and the length of the working day emerged but were left untended.

Tactically, the Know Nothings focused their attention at the state and municipal levels of electoral politics drawing on their secret organizations to mobilize voters to head to the polls and reject traditional politicians. They were most successful here in Massachusetts, when voters in 1854 swept into office Henry J. Gardiner as Governor and nearly all 400 races for the senate and house of representatives. Races from Maine to Louisiana and California saw gains from Know Nothing candidates, moving Charles Francis Adams of Massachusetts to state “There has been no revolution so complete since the organization of government.” Adherents replaced professional politicians, most evidenced in Massachusetts by the influx of clergymen replacing lawyers in elected positions.

The parallels to 2015 resound – anti-immigration in the rhetoric of “deny entry to all Muslims” and “build a wall;” anti-political parties in the rhetoric of “I am not Washington’s candidate;” secret political organizations in the fund-raising behind super-PACs; the tactics of state and local mobilizing paying off in gerrymandered and now permanently safe electoral districts in the House of Representatives; the “purity of the ballot box” in the attempted legislated election restrictions making it harder for minorities to cast their ballot.

One aspect of the current version, though, does not track with its earlier model. While the 1850s movement did not embrace a lack of knowledge, the 2015 version can lay claim to the connotations of ignorance in Know-ing Nothing, especially when one of the candidates derides the field for its “fantasy” policy proposals. Ohio Governor John Kasich seemed to be mimicking another one-time candidate, former Governor of Louisiana, Bobby Jindahl, who, in 2013, urged Republicans to “stop being the stupid party. It’s time for a new Republican Party that talks like adults.” Instead of answering they “know nothing” when asked a tough question, the candidates resort to an attack on the questioner, for his or her audacity, unfairness or meanness. Knowing nothing or very little can extend to other statements: listing five cabinet departments for elimination that included naming the same department twice; the unwillingness to walk back claims of thousands of people from New Jersey cheering the collapse of the World Trade Towers on September 11; the claim that Obamacare is the worst thing to happen in this country since slavery.

By spouting ignorance, this year’s crop of politicians is making good on Melville’s dictum of delivering fear. In considering all they advocate, though, that might just be the up side. In fact, they could be driving the ship of state in pursuit of a white whale, with its disastrous ending.

This piece also appeared on History News Network and in the Berkshire Eagle.

Getting to the future history of ISIS

Posted by John Dickson in History ahead, International, Personal memory on November 23, 2015

U.S. Embassy in Ottawa. Photo, Google Eearth

“One day those barriers will come down.” I was referring to the big concrete, jersey barriers surrounding the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa. Since they took up a lane of traffic in the downtown area, they were the target of criticism by the city’s residents whose commutes were delayed. This security precaution was needed, though, as the Embassy building stood wedged in between two busy streets.

I had added this phrase to the Ambassador’s remarks for the ceremony we were planning to mark the fourth anniversary of the September 11 attacks. History was my guidance, specifically the memory of Ronald Reagan at the Brandeburg Gate in 1987, demanding that Mikhail Gorbachev tear down the wall separating East from West Berlin. Reagan’s remarks seemed preposterous at the time, a sound-bite that would have no effect on the Soviets, even if Gorbachev had been pursuing seeking an opening with the west at the time.

A young speechwriter named Peter Robinson had inserted the “tear down the wall” words into Reagan’s speech, admitting decades later in Prologue, the National Archives magazine, that he practically stole them from a German woman at a dinner party. She had told the gathering, “If this man Gorbachev is serious with his talk of glasnost and perestroika, he can prove it. He can get rid of this wall.”

Robinson included those words in his drafts, and, he encountered resistance in the clearance process throughout the bureaucracy, all the way up to the most senior levels. The State Department and the National Security Council objected, preparing as many as seven of their own drafts. Robinson recounted that the objections clustered around that phrase: “It was naïve. It would raise false hopes. It was clumsy. It was needlessly provocative.” These words had the potential to derail progress; now Gorbachev could never tear down the wall, or he would seem to be acquiescing to Reagan’s demand. But, it was the one line in the speech that Reagan himself liked, and it stayed in.

That line did become the sound-bite for the speech, an in-your-eye poke at the Soviet Union. Initially, it was nothing more than that, a throw-away line designed for one evening’s news. Its perception as naïve vanished when three and a half years later, the wall did fall, torn down not by Gorbachev, but by citizens on both sides of the barrier.

Most of all, Reagan’s phrase articulated the unthinkable. We had lived with the Berlin Wall for decades; the Cold War and nuclear threats for longer. That was our present, and we lacked the vision to imagine a different future. Call it naïve or grandstanding, a one night line, but Reagan had painted a future that did not have to be a continuation of the present.

Back in Ottawa, the phrase in the Ambassador’s speech seemed naive as well. Inside the Embassy we debated whether to use the image, with our security officers adamant that it would only remind residents about the barriers and their delayed commutes, opening up again the clamor for their removal. We ended up using it, but fourteen years after 9/11, the jersey barriers still surround the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa.

The attacks in Paris last Friday mean that the prospects of removing those concrete barriers are further away than at any time since they were installed. Those attacks mean there is no alternative right now other than to ramp up security, to work with our partners in defeating the threat that ISIS poses.

Yet, my memories of Ottawa and the lessons of the Berlin Wall speak to our present situation, instructive in helping us imagine a different future. Those barriers will not always be there. ISIS will one day take its place in history books alongside the Barbary pirates. Does anyone really doubt that?

But there are alternatives right now, different from turning our back on our values, on the very ideals that we time and time again forget in moments of crisis. As we imagine how historians will write about this era in 50 or 100 years, do we want that narrative to compare our gut reactions to refuse entry to refugees from Syria and elsewhere with our failure to accept Jewish refugees in World War II. They are fleeing Syria because of ISIS, because of unending war. Historian might compare our willingness to trample on privacy and free speech rights with the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 or the Sedition Act of 1918 or Joe McCarthy in the Cold War.

Historians in the future might also identify the impact of our enduring values that still hold out hope to those beyond our borders. Yes, the failures to live up to those ideals are real, but so are the tools to reveal those failures and to seek redress. We have to remember it was these ideals, much more than Reagan’s six words, that ultimately led people to tear down the Berlin Wall, in their pursuit of a different way of life, of an open society, with opportunities and freedoms. We need confidence in those ideals to lead the way towards the alternative vision that ISIS paints. Call me naïve.

This post originally appeared on History News Network.

Preserving a school in Africa

Posted by John Dickson in International, Personal memory, Preservation on November 5, 2015

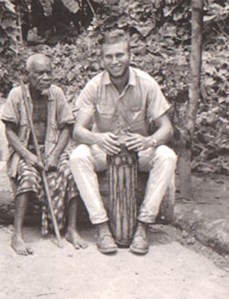

The woman we came to know as Adele grabbed the photo. Her loud exclamation in Fang, the local language, provoked a burst of laughter among the gathered villagers. I leaned over to our host, Gaston, for an explanation. He had passed around the photos we brought, and he told us that she wanted to take the picture home. It was a black and white photo of a young Peace Corps volunteer playing an African drum, seated next to a village chief, circa 1964.

Those in the open air shelter recognized the young man as Gerard, who had led a team of seven similarly fit, young men in 1964 to the village of Doumandzou to build a primary school. The group of villagers gathered 50 years later to meet us, a small group of volunteers who had come back to Gabon to fix up the school that had fallen into disrepair. We brought with us a handful of photos that Jerry (Gerard in French) Anderson had sent us to see if there were memories and traces of the group of seven who had spent less than a year in the village. To our surprise and delight, there were.

Adele had been about ten years old when the group of seven descended on her house, which her father turned over to them for their lodging while they built the school. If there was any doubt to her memory, Adele later rattled off the names of four of the volunteers, matching the list Jerry had sent us – Thomas, Etienne (Steve), Robert and, of course, Gerard. The others in the group were John, James, and Bill.

We were in Doumandzou as part of a small project we had dreamed up after a reunion of volunteers who had been in Gabon in the 1970s. We launched a non-profit and called it Encore de la Paix, a play on the French for Peace Corps (Corps de la Paix.) With a fiscal sponsor taking care of tax deductions for us, we started fund-raising for the materials to fix up the school. All told, we raised about $20,000 from friends and family members and Citibank Gabon. Paying our own way over, we descended on Doumandzou in January 2015.

Fifty years after they were built, the school and the two teachers houses were indeed in dire need of repairs. The laterite foundations and cement block walls still stood, but much of the wood for the doors and windows had fallen victim to the weather and insects. The tin roofs had come off most of the teachers’ houses, exposing the interior to rain and wind. Few of the vertical wooden planks remained in the school windows, replaced by temporary boards and tin to keep the village goats from hopping into the classroom at night for shelter. Nothing similar was done on the houses that had been vacant for years, so goats had taken over that space, as evidenced by the layers of their excrement on some of the floors. The forest was rapidly moving to take over the houses, with vines and trees running through them, along with carpet-like moss on the floors.

Fifty years is a long time, and while the school showed signs of age, the memories of the villagers for the seven volunteers remained fresh. Besides Adele, a jovial elderly man named Essame Obame Pascal, introduced himself as the mason for the original construction. Even people who had no first-hand recollection of the seven knew that the spring on the north side of village had been discovered by Robert, one of the original group. The spring still runs today, and its clear, clean water provides cooking and drinking water to those willing to make the short walk down a steep hill, and back up again balancing a heavy bucket on their heads. Gaston, who was a young boy when the school was built, is trying to pump the water up from the spring to a cistern where it can meet village needs more readily.

Working on the school, we felt at times like archaeologists, and, as we scraped, tore away, demolished and pushed back nature, the stories of the earlier volunteers came through in the construction itself. One day, while in one of the classrooms making the cement bricks for the new windows, I looked up at the wall, and noticed large figures behind where the blackboard had stood. We had taken down the blackboard a few days earlier and had been walking around the classroom, sweeping and cleaning it out, but had not focused on the painted message. I saw a number, and then a few more, and then put them together, realizing it was the year “1965.” Next to it were the initials “JA” which we knew right away were Jerry Anderson. There were two more initials, a “P” and either a “C” or a “D.” Since PD made no sense to us, we concluded it was PC, for Peace Corps. Not hieroglyphics or traditional symbols, but still a message to us from 50 years prior.

Working on the school, we felt at times like archaeologists, and, as we scraped, tore away, demolished and pushed back nature, the stories of the earlier volunteers came through in the construction itself. One day, while in one of the classrooms making the cement bricks for the new windows, I looked up at the wall, and noticed large figures behind where the blackboard had stood. We had taken down the blackboard a few days earlier and had been walking around the classroom, sweeping and cleaning it out, but had not focused on the painted message. I saw a number, and then a few more, and then put them together, realizing it was the year “1965.” Next to it were the initials “JA” which we knew right away were Jerry Anderson. There were two more initials, a “P” and either a “C” or a “D.” Since PD made no sense to us, we concluded it was PC, for Peace Corps. Not hieroglyphics or traditional symbols, but still a message to us from 50 years prior.

On another day, a bulldozer owned by the Chinese logging company in the next village, came through, and offered to clear away the encroaching brush of the forest around the school and the teachers’ houses. As the dozer pushed the forest back 50 yards or so, a tin fence appeared; then we noticed that the fence had a roof. We thought it was a shed, but Adele told us that it had been built by the earlier volunteers for the teachers’ houses. Upon investigation, we saw it was an outdoor latrine, still serviceable and relatively clean. With further clearing by villagers to push back some of the garbage strewn about near the school amidst the growth of plants, bushes and trees, yet another latrine was uncovered, this one built for the use of students at the school. Inside was an old, wooden brick mold, used by the 60s volunteers to make their cinder blocks.

To those of us who served as volunteers, Peace Corps was more than just a job, or a development project. It was about a connection to the people in the communities where we served. Halfway through the project, I received an e-mail from Jerry Anderson, who was as surprised as we were that the villagers remembered so much. Most Peace Corps volunteers readily acknowledge how important the experience was to us, how it reshaped our lives. It was always harder, though, to assess the impact of our presence on the communities where we lived and worked for two years. Those in the village remembered Jerry and his group; they attributed the school, the houses, the latrines and the fresh water spring to them, but also remembered them as real people, as friends.

These schools in Gabon stand out. More than for their slightly different design, they stand out for the memories attached to the buildings, for the short periods of intense contact, visible reminders that Americans lived and worked side-by-side by Gabonese in their remote villages. The schools are the visible reminders of a moment when the U.S. once reached out to the world with the optimism and energy of a President who realized a vision to engage and learn about the farthest corners of the world. In those places, far from the view of aid agencies and embassies and politicians, these buildings also testify to the open-armed hospitality of the hosts, who, by welcoming these strangers, tolerating our errors, and teaching us, made us all realize our common humanity. These are buildings — and ideals — worth preserving and renewing.

These schools in Gabon stand out. More than for their slightly different design, they stand out for the memories attached to the buildings, for the short periods of intense contact, visible reminders that Americans lived and worked side-by-side by Gabonese in their remote villages. The schools are the visible reminders of a moment when the U.S. once reached out to the world with the optimism and energy of a President who realized a vision to engage and learn about the farthest corners of the world. In those places, far from the view of aid agencies and embassies and politicians, these buildings also testify to the open-armed hospitality of the hosts, who, by welcoming these strangers, tolerating our errors, and teaching us, made us all realize our common humanity. These are buildings — and ideals — worth preserving and renewing.