Archive for category International

Is there a role for apology in U.S. foreign relations?

Posted by John Dickson in International, Public Affairs on January 21, 2016

The apology that a U.S. sailor gave after being detained by Iranian security forces in Iranian waters has set off a firestorm of criticism over the humiliation of our military. The video that was taken by Iranian soldiers saw the man identified as the commander of the U.S. vessel as saying, “It was a mistake that was our fault and we apologize for our mistake. It was a misunderstanding. We did not mean to go into Iranian territorial water. The Iranian behavior was fantastic while we were here. We thank you very much for your hospitality and your assistance.”

Cries of a “disgrace” and “humiliating” were heard by those who could not bring themselves to credit the diplomats with the sailors’ release and the avoidance of an international incident that could have derailed not only the nuclear deal with Iran, but also, we have since learned, an exchange of prisoners that had been the subject of negotiations for well over a year. One Congressman, Tom Rooney, from Florida and a member of the House Select Permanent Intelligence Committee, implied that the State Department had instructed the sailors to “make that kind of statement.” The State Department was vigorous in its denial that an apology had been issued in order to obtain the release of the sailors.

Absent from the back and forth of accusation and denial is any discussion of the merits of apology, either as national policy or behavior, towards foreign or domestic parties.

The rush to reject apology makes one wonder what happens to the approach to family disputes. Is an apology under those circumstances a sign of weakness, or is it a recognition that the path towards resolution might require an apology?

For sure, foreign policy is not marital reconciliation. Yet, history shows apologies have been an element of U.S. behavior, at home and abroad.

Coincidentally, the sailor’s apology came within days of the anniversary of the U.S. overthrow of the legitimate ruling monarchy of Hawaii. On the 100th anniversary of that event, a bipartisan majority in Congress issued a resolution apologizing to “to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893” and for the “deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.”

Other examples spring readily to mind: the issuance of apology to and even compensation paid to the Japanese-Americans sent to detention camps during World War II (an event that Donald Trump cited as justification to ban the entry of all Muslims into the U.S.)

Less well known was the first visit to Mexico by a sitting U.S. President, Harry Truman, in 1947. Truman did not have to utter the precise words of apology as he laid a wreath at the Mexican monument to their Niños Héroes on the eve of the centennial of the war with Mexico which saw the loss of nearly half of its territory. Mexicans not only took the gesture as an apology, but, instead of seeing it as weakness, they received it in the way it was offered. They enthusiastically embraced Truman as a “new champion of American solidarity and understanding,” in the words of Mexican Foreign Minister Ramon Beteta. Others went further, as one eyewitness was quoted as saying, “one hundred years of misunderstanding and bitterness wiped out by one man in one minute.” The response led President Clinton to repeat the gesture in 1997 when he visited Mexico City.

U.S. allies around the world are less reluctant to abjure apology as a component in their foreign relations. In 2007, the British government expressed regret and authorized payments of £20 million to compensate victims tortured by its forces during the Mau Mau rebellion against British rule in Kenya in the 1950s. Just last month, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offered “apologies and remorse” for the “immeasurable and painful experiences” suffered by women in Korea forced to provide sexual services to Japanese soldiers during the World War II. As part of a settlement with the government of South Korea, Japan agreed to make payments to a fund for victims. Other examples include Canada’s apology in 2008 to First Nations peoples for the system of Indian Residential Schools and Australia’s apology in 2014 to Indonesia for naval ships straying into Indonesian waters without permission.

The apology last week in the Persian Gulf differed from other examples in that it was likely a spur-of-the-moment decision by the commander, as opposed to national policy arrived at after considerable discussion, and in the Hawaii and Mexico examples, after 100 years has lapsed. More recently, though, we have the cases of the U.S. and NATO forces who apologized for military operations in Afghanistan that result in civilian deaths.

Presidential politics make the issue of apology harder. Taking a cue from Mitt Romney’s 2010 campaign book titled, No Apology: The Case for American Greatness, candidates and pundits on the eve of the Iowa caucuses rushed to criticize weakness, claiming as well that the Iranians violated the Geneva Convention and its clauses related to treatment of prisoners in wartime. Such short memories. Less than ten years ago, these same individuals were trying to back away from and even rewrite that convention to suit U.S. methods of interrogation.

A refusal to accept any measure of accountability for U.S. behavior implies that no actions have been taken that have been either mistaken or misguided or immoral. Or that they were justified to make America great.

In discussing the negotiations that Secretary Kerry and his team had with Iran over the prisoner exchange, he recalled that the Iranians repeatedly raised the 1953 coup organized by U.S. intelligence to overthrow the legitimately elected Mohammad Mossadegh as President of Iran. The Iranians remember, and we deny.

I do subscribe to the notion of greatness for my country that I served for almost 30 years. It is a greatness, though, that has the strength, confidence and wisdom to hold itself accountable for its errors and to aspire to do better.

This post originally appeared on History News Network.

Getting to the future history of ISIS

Posted by John Dickson in History ahead, International, Personal memory on November 23, 2015

U.S. Embassy in Ottawa. Photo, Google Eearth

“One day those barriers will come down.” I was referring to the big concrete, jersey barriers surrounding the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa. Since they took up a lane of traffic in the downtown area, they were the target of criticism by the city’s residents whose commutes were delayed. This security precaution was needed, though, as the Embassy building stood wedged in between two busy streets.

I had added this phrase to the Ambassador’s remarks for the ceremony we were planning to mark the fourth anniversary of the September 11 attacks. History was my guidance, specifically the memory of Ronald Reagan at the Brandeburg Gate in 1987, demanding that Mikhail Gorbachev tear down the wall separating East from West Berlin. Reagan’s remarks seemed preposterous at the time, a sound-bite that would have no effect on the Soviets, even if Gorbachev had been pursuing seeking an opening with the west at the time.

A young speechwriter named Peter Robinson had inserted the “tear down the wall” words into Reagan’s speech, admitting decades later in Prologue, the National Archives magazine, that he practically stole them from a German woman at a dinner party. She had told the gathering, “If this man Gorbachev is serious with his talk of glasnost and perestroika, he can prove it. He can get rid of this wall.”

Robinson included those words in his drafts, and, he encountered resistance in the clearance process throughout the bureaucracy, all the way up to the most senior levels. The State Department and the National Security Council objected, preparing as many as seven of their own drafts. Robinson recounted that the objections clustered around that phrase: “It was naïve. It would raise false hopes. It was clumsy. It was needlessly provocative.” These words had the potential to derail progress; now Gorbachev could never tear down the wall, or he would seem to be acquiescing to Reagan’s demand. But, it was the one line in the speech that Reagan himself liked, and it stayed in.

That line did become the sound-bite for the speech, an in-your-eye poke at the Soviet Union. Initially, it was nothing more than that, a throw-away line designed for one evening’s news. Its perception as naïve vanished when three and a half years later, the wall did fall, torn down not by Gorbachev, but by citizens on both sides of the barrier.

Most of all, Reagan’s phrase articulated the unthinkable. We had lived with the Berlin Wall for decades; the Cold War and nuclear threats for longer. That was our present, and we lacked the vision to imagine a different future. Call it naïve or grandstanding, a one night line, but Reagan had painted a future that did not have to be a continuation of the present.

Back in Ottawa, the phrase in the Ambassador’s speech seemed naive as well. Inside the Embassy we debated whether to use the image, with our security officers adamant that it would only remind residents about the barriers and their delayed commutes, opening up again the clamor for their removal. We ended up using it, but fourteen years after 9/11, the jersey barriers still surround the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa.

The attacks in Paris last Friday mean that the prospects of removing those concrete barriers are further away than at any time since they were installed. Those attacks mean there is no alternative right now other than to ramp up security, to work with our partners in defeating the threat that ISIS poses.

Yet, my memories of Ottawa and the lessons of the Berlin Wall speak to our present situation, instructive in helping us imagine a different future. Those barriers will not always be there. ISIS will one day take its place in history books alongside the Barbary pirates. Does anyone really doubt that?

But there are alternatives right now, different from turning our back on our values, on the very ideals that we time and time again forget in moments of crisis. As we imagine how historians will write about this era in 50 or 100 years, do we want that narrative to compare our gut reactions to refuse entry to refugees from Syria and elsewhere with our failure to accept Jewish refugees in World War II. They are fleeing Syria because of ISIS, because of unending war. Historian might compare our willingness to trample on privacy and free speech rights with the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 or the Sedition Act of 1918 or Joe McCarthy in the Cold War.

Historians in the future might also identify the impact of our enduring values that still hold out hope to those beyond our borders. Yes, the failures to live up to those ideals are real, but so are the tools to reveal those failures and to seek redress. We have to remember it was these ideals, much more than Reagan’s six words, that ultimately led people to tear down the Berlin Wall, in their pursuit of a different way of life, of an open society, with opportunities and freedoms. We need confidence in those ideals to lead the way towards the alternative vision that ISIS paints. Call me naïve.

This post originally appeared on History News Network.

Preserving a school in Africa

Posted by John Dickson in International, Personal memory, Preservation on November 5, 2015

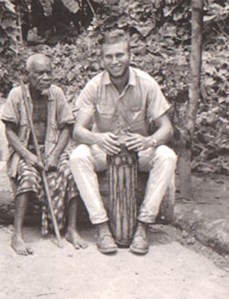

The woman we came to know as Adele grabbed the photo. Her loud exclamation in Fang, the local language, provoked a burst of laughter among the gathered villagers. I leaned over to our host, Gaston, for an explanation. He had passed around the photos we brought, and he told us that she wanted to take the picture home. It was a black and white photo of a young Peace Corps volunteer playing an African drum, seated next to a village chief, circa 1964.

Those in the open air shelter recognized the young man as Gerard, who had led a team of seven similarly fit, young men in 1964 to the village of Doumandzou to build a primary school. The group of villagers gathered 50 years later to meet us, a small group of volunteers who had come back to Gabon to fix up the school that had fallen into disrepair. We brought with us a handful of photos that Jerry (Gerard in French) Anderson had sent us to see if there were memories and traces of the group of seven who had spent less than a year in the village. To our surprise and delight, there were.

Adele had been about ten years old when the group of seven descended on her house, which her father turned over to them for their lodging while they built the school. If there was any doubt to her memory, Adele later rattled off the names of four of the volunteers, matching the list Jerry had sent us – Thomas, Etienne (Steve), Robert and, of course, Gerard. The others in the group were John, James, and Bill.

We were in Doumandzou as part of a small project we had dreamed up after a reunion of volunteers who had been in Gabon in the 1970s. We launched a non-profit and called it Encore de la Paix, a play on the French for Peace Corps (Corps de la Paix.) With a fiscal sponsor taking care of tax deductions for us, we started fund-raising for the materials to fix up the school. All told, we raised about $20,000 from friends and family members and Citibank Gabon. Paying our own way over, we descended on Doumandzou in January 2015.

Fifty years after they were built, the school and the two teachers houses were indeed in dire need of repairs. The laterite foundations and cement block walls still stood, but much of the wood for the doors and windows had fallen victim to the weather and insects. The tin roofs had come off most of the teachers’ houses, exposing the interior to rain and wind. Few of the vertical wooden planks remained in the school windows, replaced by temporary boards and tin to keep the village goats from hopping into the classroom at night for shelter. Nothing similar was done on the houses that had been vacant for years, so goats had taken over that space, as evidenced by the layers of their excrement on some of the floors. The forest was rapidly moving to take over the houses, with vines and trees running through them, along with carpet-like moss on the floors.

Fifty years is a long time, and while the school showed signs of age, the memories of the villagers for the seven volunteers remained fresh. Besides Adele, a jovial elderly man named Essame Obame Pascal, introduced himself as the mason for the original construction. Even people who had no first-hand recollection of the seven knew that the spring on the north side of village had been discovered by Robert, one of the original group. The spring still runs today, and its clear, clean water provides cooking and drinking water to those willing to make the short walk down a steep hill, and back up again balancing a heavy bucket on their heads. Gaston, who was a young boy when the school was built, is trying to pump the water up from the spring to a cistern where it can meet village needs more readily.

Working on the school, we felt at times like archaeologists, and, as we scraped, tore away, demolished and pushed back nature, the stories of the earlier volunteers came through in the construction itself. One day, while in one of the classrooms making the cement bricks for the new windows, I looked up at the wall, and noticed large figures behind where the blackboard had stood. We had taken down the blackboard a few days earlier and had been walking around the classroom, sweeping and cleaning it out, but had not focused on the painted message. I saw a number, and then a few more, and then put them together, realizing it was the year “1965.” Next to it were the initials “JA” which we knew right away were Jerry Anderson. There were two more initials, a “P” and either a “C” or a “D.” Since PD made no sense to us, we concluded it was PC, for Peace Corps. Not hieroglyphics or traditional symbols, but still a message to us from 50 years prior.

Working on the school, we felt at times like archaeologists, and, as we scraped, tore away, demolished and pushed back nature, the stories of the earlier volunteers came through in the construction itself. One day, while in one of the classrooms making the cement bricks for the new windows, I looked up at the wall, and noticed large figures behind where the blackboard had stood. We had taken down the blackboard a few days earlier and had been walking around the classroom, sweeping and cleaning it out, but had not focused on the painted message. I saw a number, and then a few more, and then put them together, realizing it was the year “1965.” Next to it were the initials “JA” which we knew right away were Jerry Anderson. There were two more initials, a “P” and either a “C” or a “D.” Since PD made no sense to us, we concluded it was PC, for Peace Corps. Not hieroglyphics or traditional symbols, but still a message to us from 50 years prior.

On another day, a bulldozer owned by the Chinese logging company in the next village, came through, and offered to clear away the encroaching brush of the forest around the school and the teachers’ houses. As the dozer pushed the forest back 50 yards or so, a tin fence appeared; then we noticed that the fence had a roof. We thought it was a shed, but Adele told us that it had been built by the earlier volunteers for the teachers’ houses. Upon investigation, we saw it was an outdoor latrine, still serviceable and relatively clean. With further clearing by villagers to push back some of the garbage strewn about near the school amidst the growth of plants, bushes and trees, yet another latrine was uncovered, this one built for the use of students at the school. Inside was an old, wooden brick mold, used by the 60s volunteers to make their cinder blocks.

To those of us who served as volunteers, Peace Corps was more than just a job, or a development project. It was about a connection to the people in the communities where we served. Halfway through the project, I received an e-mail from Jerry Anderson, who was as surprised as we were that the villagers remembered so much. Most Peace Corps volunteers readily acknowledge how important the experience was to us, how it reshaped our lives. It was always harder, though, to assess the impact of our presence on the communities where we lived and worked for two years. Those in the village remembered Jerry and his group; they attributed the school, the houses, the latrines and the fresh water spring to them, but also remembered them as real people, as friends.

These schools in Gabon stand out. More than for their slightly different design, they stand out for the memories attached to the buildings, for the short periods of intense contact, visible reminders that Americans lived and worked side-by-side by Gabonese in their remote villages. The schools are the visible reminders of a moment when the U.S. once reached out to the world with the optimism and energy of a President who realized a vision to engage and learn about the farthest corners of the world. In those places, far from the view of aid agencies and embassies and politicians, these buildings also testify to the open-armed hospitality of the hosts, who, by welcoming these strangers, tolerating our errors, and teaching us, made us all realize our common humanity. These are buildings — and ideals — worth preserving and renewing.

These schools in Gabon stand out. More than for their slightly different design, they stand out for the memories attached to the buildings, for the short periods of intense contact, visible reminders that Americans lived and worked side-by-side by Gabonese in their remote villages. The schools are the visible reminders of a moment when the U.S. once reached out to the world with the optimism and energy of a President who realized a vision to engage and learn about the farthest corners of the world. In those places, far from the view of aid agencies and embassies and politicians, these buildings also testify to the open-armed hospitality of the hosts, who, by welcoming these strangers, tolerating our errors, and teaching us, made us all realize our common humanity. These are buildings — and ideals — worth preserving and renewing.

E-mails, history and diplomats

Posted by John Dickson in History ahead, International, Personal memory on March 17, 2015

Imagine the conversation that Hillary Clinton had with her Information Technology people when she started her job as Secretary of State. First of all, she probably didn’t have one, but her staff did, on behalf of her wishes. “The Secretary does not want to have an official account on the State Department system,” they would have said. “She will use her own private e-mail and server for her electronic communications.”

Loyally, like most in the Department, the professional IT folks nodded and went to work to MAKE IT HAPPEN. Their concerns, if they voiced any at all, would have fallen in the security arena. What they likely did not say was anything about the need to keep a historical record.

The reality is that for most of the communications coming from the Secretary’s office, she relied on her staff who probably all had official accounts, as well as their own private mail. As Gail Collins points out in her op-ed in the New York Times, the former Secretary’s reference to 60,000 e-mails during her tenure turns out to be roughly 40 a day. It’s not inconceivable that her many staff churned out more than that on her behalf in ten minutes. All of those messages are, we can assume, on the official system.

The problem with the exclusive use of private e-mail that many of her would-be detractors are focusing on is, incredibly, Benghazi, and then security. However, by deciding what the public should and should not see, the former Secretary simply leaves to the imagination what will not see the light of day. Ms. Clinton says it is personal material, and undoubtedly there are plenty of those. Likely there are also messages related to her past and perhaps future status as a politician, interacting with the large retinue of friends and donors, responding to their requests for favors, small and large. Not unusual for any politician holding any government office.

Surely Ms. Clinton or someone on her staff must have realized the historic value of her documents, if only for her memoir that she was sure to (and did) write. Why save documents only for her book? She makes the claim that her business e-mails to those in the Department could be accessed through the recipients, but she did not send e-mails to just other State Department officials. Further, if her staff were using official accounts in sending e-mails to carry out her instructions, it is unclear who would know which of these messages were valued for the historic record.

It’s not just the absence of the former Secretary’s communications that presents a challenge to future historians. While no one is suggesting this as a reason for her foregoing the State Department server, the chilling effect of leaks (such as Wiki-leaks or Snowden cases) on official communications is taking a toll on the written record. Rather than write cables, the use of e-mail is more pervasive and when the issue is very sensitive, phone calls are taking over as the medium of choice.

What Secretary Clinton’s private e-mail use also encapsulates is the broader issue of how the Department of State does not take full advantage of its own history in the conduct of the country’s foreign relations. To their credit, it was staff in the Office of the Historian that first brought this issue to light, in seeking to gain access for its archives to these documents. That Office and their on-line presence, through its series on Foreign Relations of the United States, has made available 450 volumes of primary source documents that have been declassified and, most recently, has begun to include material from other foreign affairs agencies. These represent an invaluable resource for scholars of U.S. foreign policy. However, it is mainly academics who mine these documents for their research. Based on my experience in the Department few of us working the multitude of issues confronting the nation in our overseas relations, drew on that resource. We did not have the time, the inclination, the skills to mine those documents as another source of “intelligence” to analyze the countries or the topics we were handling. The fact that the Historian’s Office is located in the Bureau of Public Affairs is a tip-off that its focus is external, not to inform current foreign policy issues. Perhaps the Bureau of Intelligence and Research where reports could be made for policy makers?

Our military devotes incredible effort and resources to learning its own history, and values history in its academies and its in-service training. They read the communications of soldiers in the preparations for battle as well as on the battlefield to understand the decisions taken. Our diplomats deserve the same attention to their history, to equip them to understand the complex, messy terrain of our relations around the world.

Obama and Netanyahu Differ on History, Not Just Iran

Posted by John Dickson in History ahead, International, Public Affairs on March 5, 2015

The differences between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Barack Obama extend beyond their views of the current negotiations to limit Iran’s capacity to develop nuclear weapons. The two leaders draw on fundamentally different lessons from history as they shape their country’s respective positions in regards to a nuclear Iran. In fact, their whole approach to using history in making their case on whether or not to engage Iran diplomatically differs.

Speaking before the Joint Meeting of Congress, the Prime Minister engaged in historical selection in looking backward to predict what might lay ahead. After the obligatory political thank you’s, Netanyahu started his speech by citing the Old Testament story of Esther, a “courageous Jewish woman” who warned the Jewish people of a plot to destroy them conceived by a Persian viceroy. He drew the direct line from the religious holiday of Purim commemorating the story of Esther to what he sees is yet another plot by a Persian ruler to destroy Israel and he cites the sitting Ayatollah’s tweets as evidence. Another Old Testament figure that Netanyahu chose to ignore is the Persian King Cyrus who ended the Babylonian captivity, called for the rebuilding of a “house of God” in Jerusalem and restored the religious vessels that his predecessor Nebuchadnezzar had taken when he destroyed the temple and the city.

Netanyahu also cites more recent history in highlighting the case of North Korea, when it reneged on its commitments to an international agreement hammered out through diplomatic negotiations to forestall the acquisition of a nuclear bomb. North Korea, like Iran, was a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Agreement. To date, North Korea is the only country to have withdrawn from the agreement, and all obligations under it to limit nuclear technology to peaceful purposes and prevent the development and spread of nuclear weapons. Here again, another historical selection overlooked by Netanyahu is South Africa, which abandoned its nuclear weapon program and signed the non-proliferation treaty in 1993.

The point is not that the appropriate historical parallels ought to be Cyrus and South Africa, but that historical precedents abound and can land on any side of a political debate.

President Obama, on the other hand, uses his understanding of history not to find past precedents but to look for present, transformative opportunities that could reshape history, as understood only by looking backward years from now.

Obama certainly knows of such historic moments. It’s not hard to anticipate the histories 50 or 100 years from now, citing his election and re-election as the first African-American President. They may also include his willingness to open a new chapter in U.S. relations with Cuba or to tackle the issue of affordable health care in this country, just to mention two. In announcing the opening of diplomatic talks with Iran in September 2013, Obama looked ahead and envisioned the possibilities of not only “a major step forward in a new relationship between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” but also one that would “help us to address other concerns that could bring greater peace and stability to the Middle East.”

Obama also recognizes that individuals who seek such opportunities run enormous risks, not just for their own political careers but for their nations that they lead. It’s why he is leaving the door open for tougher sanctions and even the use of military options should Iran decide to use these negotiations as a cover to work towards producing nuclear weapons. He does not want those histories in the future to write of him as another architect of appeasement. The roads he has chosen to walk are littered with obstacles and critics. However, he also acknowledges that the alternatives on Iran, however politically expedient they may be in dealing with crises, do not offer to resolve them, simply delay them, perhaps for another President or Prime Minister. His model, after all, is Lincoln, not Buchanan.

Both leaders take a long view of history, but while Netanyahu’s view goes backward, Obama’s looks forward. When Netanyahu looks forward, he sees only weeks, to the next election in Israel on March 17, or to inject himself into the current political stalemate in Washington. David Remnick’s profile of Obama in the pages of the New Yorker in January 2014 quoted aides repeatedly discussing Obama’s sense of understanding his actions under the long telescope of history. Obama told Remnick that “at the end of the day we’re part of a long-running story. We just try to get our paragraph right.”

There is a great distance to go before reaching any accord with Iran over its nuclear program and its commitments under the Non-Proliferation Treaty and an even greater distance to restoring diplomatic relations with Iran. But history is the story of change, and that change does not happen without taking the first steps, as risky as they might seem. Netanyahu uses history to avoid the first step; Obama looks way down the road to see where that first step might lead.

This post originally appeared on History News Network.