John Dickson

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Homepage: https://timecapsulepilot.wordpress.com

Torture – Who We are and Who we aspire to be

Posted in International, Public Affairs on December 16, 2014

The first photographs that surfaced on Abu Ghraib in the spring of 2004 were so jarring, I thought at first that they were doctored. The hope was that these were some propagandistic, photo-shopped images designed to put the U.S. in the worst possible light.

Ten years later, and we as a nation are still struggling over the issue of detentions and interrogations that cross the line into the realm of torture. While it was military intelligence and their contractors in the docket at Abu Ghraib, the report by the Senate Intelligence Committee this week confined itself to those practices employed by the CIA.

Ten years later, and we as a nation are still struggling over the issue of detentions and interrogations that cross the line into the realm of torture. While it was military intelligence and their contractors in the docket at Abu Ghraib, the report by the Senate Intelligence Committee this week confined itself to those practices employed by the CIA.

In the days since its release, many of our leaders cast the report in a tone of optimism about our values and the self-correcting nature of our system. Vice President Biden referred to the report as a “badge of honor,” alleging that while all countries make mistakes, few have the strength to acknowledge the errors. The Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee Dianne Feinstein closed her statement from the Senate floor declaring that this “report will carry the message ‘never again.’” She was followed by Senator John McCain, who was himself a victim of torture while a prisoner in Vietnam. He couched his reaction to the report in terms of our character as a nation: “this question isn’t about our enemies; it’s about us. It’s about who we were, who we are and who we aspire to be. It’s about how we represent ourselves to the world.” President Obama struck a similar note when he called the practices outlined in the report, “contrary to who we are, contrary to our values.”

Most Americans would like to agree with these sentiments; that we do not torture, that this report does not reflect the values of the nation. However, several points in the report may indicate otherwise, that these practices likely occurred more often than we know.

Senator Feinstein in her statement from the Senate floor on December 8 made two references that suggest a larger history of use of torture methods by the CIA. Both were embedded in communications from a high-level CIA official, John Helgerson. First, she made the point that the agency did not even learn from its own history, citing an e-mail from Helgerson to the CIA Director Michael Hayden in 2005, “… we have found that the Agency over the decades has continued to get itself in messes related to interrogation programs for one overriding reason: we do not document and learn from our experience – each generation of officers is left to improvise anew, with problematic results for our officers as individuals and for our Agency.” (emphasis mine) At the time, Helgerson was the Inspector General (IG) of the agency and was conducting a review of the practice in his capacity as an independent, internal watchdog reviewing government programs for waste, fraud and abuse. Helgerson’s review of the detention and interrogations program at the CIA may have been too intrusive as the CIA Director Hayden himself launched an inquiry into its own Inspector General’s office, according to the New York Times.

The issue that remains, though, in the Senate report is the nature of that history “over the decades” that Helgerson mentioned. His own Inspector General Report completed in May 2004, was not publicly released until April 2009, and then it was heavily redacted. That report provided this historic outline:

- “The Agency has had intermittent involvement in the

interrogation of individuals whose interests are opposed to those of

the United States. After the Vietnam War, Agency personnel

experienced in the field of interrogations left the Agency or moved to

other assignments. In the early 1980s, a resurgence of interest in

teaching interrogation techniques developed as one of several

methods to foster foreign liaison relationships. Because of political

sensitivities the then-Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DDCI)

forbade Agency officers from using the word “interrogation.” The

Agency then developed the Human Resource Exploitation (HRE) .

training program designed to train foreign liaison services on

interrogation techniques.”

Not only was the U.S. involved in such interrogations but we were training foreign countries on the methods. Such training ended in 1986 when abuses were identified in Latin America. Helgerson’s 2004 report also referred to the 1984 investigation of two CIA officers who had been investigated following the death of an individual they interrogated.

Senator Feinstein’s second reference to Helgerson may shed light on specific timing of other previous incidents. She cited a letter he sent to the Senate Intelligence Committee on January 8, 1989. Helgerson, then the Director of Congressional Affairs at the CIA, was evaluating the effectiveness of such techniques, concluding that “inhumane physical or psychological techniques are counterproductive because they do not produce intelligence and will probably result in false answers.” Helgerson’s letter was in response to a committee inquiry over a topic that remains unnamed.

We do know that Helgerson had been called to hearings in the late 1980s on the Iran-Contra funding and on the role of the CIA in drug trafficking, but there is no indication that his reference to inhuman techniques was in either of those contexts.

The references to John Helgerson in the Senate report released this week do seem to indicate that we have a broader history with these interrogation practices than we know about. In that light, they do also require us to reconsider who we are and who we aspire to be. Such a reconsideration may require more actions than just releasing this report.

In the ten years since Abu Ghraib, only low-level soldiers were convicted of any wrong-doing. It has been the same ten years since Helgerson’s IG report; we do not know what his recommendations were, nor if they were carried out. We only know that it took five years following both Abu Ghraib and that IG report for a new President to put an end to the interrogations. We also remember that early in his tenure, President Obama announced his intention to close the detention facilities at Guantanamo. Further, in early 2009, the Justice Department conducted two separate investigations into the CIA detention and interrogation program to determine if criminal charges could be brought. The department decided to decline, concluding that those responsible “acted in good faith and within the scope of the legal guidance given by the Office of Legal Counsel regarding the interrogation of detainees.”

Short of prosecuting individuals involved, though, two other steps would help to realign our actions with who we aspire to be. First would be the ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, that calls on countries to allow for inspections of detention facilities as a means to prevent torture. While we ratified and signed the original convention in 1994, we have yet to approve this addendum that came into force in 2006. A second step would be to move as fast as possible to close the prison at Guantanamo, putting terror suspects into the U.S. judicial system.

The politics of these steps make their likelihood remote indeed. However, in order to assure that the U.S. really is committed “never again” to torture, such actions may be necessary. Then our conduct would more closely align with who we think we are and who we aspire to be.

This article first appeared on History News Network on December 14, 2014:

Michael Brown and the Midterm Elections

Posted in History ahead, Public Affairs on December 4, 2014

What is the connection between the Republican takeover of the Senate in the midterm elections and the grand jury decision in Ferguson, Missouri not to indict the policeman who shot Michael Brown? I would not have made any myself, if I did not happen to be reading Robert Caro’s series on Lyndon Johnson. Reading Caro helps draw lines from the two events back to the 1930s when they intersect with earlier obstructionist Senators blocking efforts to pass anti-lynching legislation, that festered grievances against racial bias in our criminal justice system. This newly strengthened Congress has made clear it will obstruct issues on the national agenda, but which ones will continue to fester for years to come?

In his third volume on Johnson’s Senate years, Master of the Senate, Caro sets up Johnson’s rise to positions of leadership with an extended history of that body, its deliberative function and the slow procedural mechanisms. The author maneuvers through several Senate eras, from its original establishment in the Constitutional as a deliberative body of six-year tenured aristocrats in order to check not only the power of the executive, but also the transitory sentiments of the popular will, as represented in the House of Representatives. The golden age of deliberation and compromise during the Senate of Webster, Calhoun and Clay gave way to an all-out brawl with the executive during reconstruction. Then, the Gilded Age ushered in an extended era of obfuscation and obstruction, broken only by a flurry of progressive bills that passed during Woodrow Wilson’s early years in the White House and then later during FDR’s first term. The rules established in the Senate allowed for a handful of leaders to manipulate parliamentary procedure and prevent bills that might reign in the excesses of business or that would ratify the Treaty of Versailles ending the “Great War,” effectively keeping the U.S. out of the League of Nations.

These precedents of delay and obstruction in the Senate paved the way for the battleground over civil rights. The procedure was the filibuster and the related provisions of cloture to cut off debate. When Congress used these tactics to obstruct a measure to integrate the armed forces following the Second World War, President Harry Truman turned to an executive order in 1948 to accomplish this, much like Obama is using his executive authority in the failure of Congress, in this case the House, to act on immigration reform.

Yet, it was the inability of Congress to outlaw lynching that the connection reaches to Ferguson, Missouri. On its face, the horrifying practice of lynching would seem to be one issue that would be easy to muster up a majority to make illegal. However, during the period between 1882 and 1968 when almost 3500 African-Americans were murdered by lynching, over 200 times bills were introduced in Congress to outlaw the extrajudicial killing. Presidents repeatedly asked Congress to pass a law, but only three times did a bill pass the House. Caro focuses on those three in his book, in 1922, 1935 and 1938, describing the use of the filibuster and the cloture rule to prevent passage of those bills in the Senate. He describes in detail the tactics of Richard Russell, the powerful Democratic Senator from Georgia, whose home town of Winder was the site of several prominent such murders. Russell couched his opposition to the lynching bill in the Constitutional prerogatives of the Senate, including the need to protect the filibuster and cloture as mechanisms to ensure checks and balances. He wanted to ensure no civil rights bill, of any ilk, would pass.

This history of extrajudicial killings weighs heavily on what has transpired in Ferguson, Missouri. While no one is calling the killing of Michael Brown a lynching, the number of protests since his death does seem to make such a link, though, at least into the extended past of unpunished killings of African-Americans. For many, what happened to Michael Brown had more to with a history of bias in the criminal justice system than the actual facts of this individual case, however tragic it was. That past that reaches back even beyond the refusal to outlaw lynchings is not even that distant, certainly well within the lifetimes of many alive today.

It can be debated what the impact on race relations today would have been if Congress had not obstructed efforts to outlaw lynching in 1938, or 1922, or even earlier. What did happen, though, in 2005, was a recognition that more should have been done. That year, the Senate adopted a resolution apologizing for its history of refusing to pass such a law. It was a non-binding resolution to correct “inaction on what were great injustices,” according to then White House Press Secretary Scott McClellan. One of the bill’s sponsors noted that “the Senate failed you and your ancestors and our nation,” in remarks before families of victims. That Senator was Mary Landrieu, a Democrat from Louisiana, who will likely lose her seat this week in a run-off election, on December 6.

The mid-term elections strengthened a Congress that has made clear it will use all its powers and procedures available to obstruct action on any number of issues of national urgency – health care for millions of uninsured, climate change, closing Guantanamo prison, immigration reform. This is not about exceeding its Constitutional authorities. Congress, over 80 years, used its own rules of filibuster and cloture to obstruct anti-lynching legislation. However, as Caro and Landrieu point out, it used its deliberative rules as an excuse for inaction, to protect narrow interests. “Failing the nation,” the Senate kept alive a bias in the criminal justice system that many see played out again in 2014 in Ferguson Missouri. On which issue will its obstruction require an apology for failing to act 50, 80, 100 years from now?

Waving the Red Flag

Posted in Immigration, International, Public Affairs on November 23, 2014

When President Obama announced this week he would use his executive powers to make immigration changes, the incoming Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell warned that “would be like waving a red flag in front of a bull.” Cries of “emperor” and “monarch” rang out from Republicans in Congress. Representative Joe Barton from Texas already saw red, claiming such executive action would be grounds for impeachment. Another representative, Mo Brooks from Alabama, called for Obama’s imprisonment.

If using executive authority constitutes an impeachable offense, then Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy should all have been removed from office. All four skirted Congress, at times overtly flouting their administrative prerogative, to implement a guest worker program.

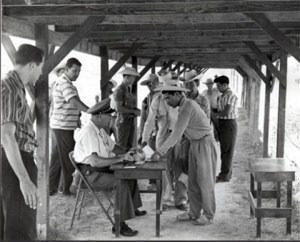

This was the “Bracero” agreement with the Government of Mexico to recruit workers during World War II, starting in 1942 but lasting beyond the war, all the way until 1964. At its height in the mid 1950s, this program accounted for 450,000 Mexicans per year coming to the U.S. to work, primarily as agricultural workers.

Several aspects of the Bracero program stand out as relevant to the impasse on immigration reform over the last 15 years. First, the program began with executive branch action, without Congressional approval. Second, negotiations with the Mexican government occurred throughout the program’s duration, with the State Department taking the lead in those talks. Finally, this guest worker initiative, originally conceived as a wartime emergency, evolved into a program in the 1950s that served specifically to dampen illegal migration.

Even before Pearl Harbor, growers in the southwest faced labor shortages in their fields and had lobbied Washington to allow for migrant workers, but unsuccessfully. It took less than five months following the declaration of war to reverse U.S. government intransigence on the need for temporary workers. Informal negotiations had been taking place between the State Department and the Mexican government, so that an agreement could be signed on April 4, 1942 between the two countries. By the time legislation had passed authorizing the program seven months later, thousands of workers had already arrived in the U.S.

The absence of Congress was not just due to a wartime emergency. On April 28, 1947, Congress passed Public Law 40 declaring an official end to the program by the end of January the following year. Hearings were held in the House Agriculture Committee to deal with the closure, but its members proceeded to propose ways to keep guest workers in the country and extend the program, despite the law closing it down. Further, without the approval of Congress, the State Department was negotiating a new agreement with Mexico, signed on February 21, 1948, weeks after Congress mandated its termination. Another seven months later, though, Congress gave its stamp of approval on the new program and authorized the program for another year. When the year lapsed, the program continued without Congressional approval or oversight.

The Bracero Program started out as a wartime emergency, but by the mid-1950s, its streamlined procedures made it easier for growers to hire foreign labor without having to resort to undocumented workers. Illegal border crossings fell.

Still, there were many problems making the Bracero Program an unlikely model for the current immigration reforms. Disregard for the treatment of the contract workers tops off the list of problems and became a primary reason for shutting the program down. However, the use of executive authority in conceiving and implementing an immigration program is undeniable.

The extent of the executive branch involvement on immigration was best captured in 1951, when a commission established by President Truman to review the status of migratory labor concluded that “The negotiation of the Mexican International Agreement is a collective bargaining situation in which the Mexican Government is the representative of the workers and the Department of State is the representative of our farm employers.” Not only was the executive branch acting on immigration, but they were negotiating its terms and conditions, not with Congress, but with a foreign country. Remarkable language, especially looking forward to 2014 when we are told that such action would be an impeachable offense.

Senator McConnell used the bullfighting analogy because the red flag makes the bull angry; following the analogy to its inevitable outcome is probably not what he had in mind. The poor, but angry bull never stands a chance. In this case, though, it won’t be those in Congress who don’t stand a chance; it will be those caught in our messy and broken immigration system.

This article first appeared on History News Network.

Using History to Resolve a Crisis

Posted in History ahead, International, Public Affairs on July 22, 2014

On this day, 89 years ago, the New York Times carried a story in its far left hand column with the headline “Long Step To Peace Is Seen By Britain in Germany’s Reply.” Absent a banner headline, it recounted the text of a diplomatic note from Germany to Great Britain about ongoing negotiations to resolve several matters growing out of the Versailles Treaty ending the Great War. These included border disputes along Germany’s western border, the inviolability of the Versailles Treaty and Germany’s entry into the League of Nations. These negotiations ultimately ended up settled in the Locarno Peace Treaties several months later, and were the basis for the Nobel Peace Prize that Britain’s Foreign Minister, Austen Chamberlain, won.

Eleven years later, Germany abrogated both the Versailles and the Locarno Treaties with its invasion of the demilitarized zone along the Rhine. The following year, Austen’s half-brother Neville became Prime Minister of Great Britain, and earnestly sought to resolve tensions in Europe by acceding to Hitler’s demands.

This article, 89 years ago today, brought to mind last week’s international crises, a trifecta of problems facing the United States:

— the downing of a Malaysian airlines passenger jet by Russian separatist in Ukraine, with some level of assistance from Russia

— an intensifying conflict in the Middle East with the Israeli ground invasion of Gaza

— the presence of 57,000 undocumented children from Central America in U.S. detention centers

These three issues cloud out other crises that just a few weeks earlier had concentrated the minds of those in charge of U.S. foreign policy: the ongoing civil war in Syria, disputed Presidential elections in Afghanistan and a brazen invasion of Iraq by extremists seeking to establish an Islamic state across territory of Iraq and Syria. Events such as these don’t leave room for truly devastating humanitarian crises that never even make it in the news, like the ongoing refugee crisis in South Sudan where 700,000 people are internally displaced and hunger is affecting millions more.

If Hillary Clinton gave the title “Hard Choices” to her memoir of her tenure as Secretary of State, John Kerry’s sequel from just last week will make her watch look fairly tame.

Each of these three major events – Ukraine, border children, Gaza ground invasion – would carry banner headlines on their own. Any newspaper’s difficult decision last week was which deserved prominence.

They also each have historical precedents that are cited and considered. Match the precedent with the crisis: Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990; Kosovo’s secession from Serbia in 2008; the Mariel boat lift in 1980 or the Haitian migrant crisis in 1994; the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 2006 or of Gaza in 2012 or 2009; the downing of a Korean airliner in 1983, or an Iranian passenger jet in 1988. None show the way to a clear cut path to resolving the crisis at hand. History can give a pretty clear map to what transpired, identifying the sequence of events and the conditions that lend a certain air of inevitability to any outcome. History is not as good as showing a way forward, especially when the choices in each of these cases are more than hard – they are messy and unpredictable in the outcomes they yield and the consequences they unknowingly generate.

So, what is the connection between a fairly mundane story 89 years ago and these major events? That ordinariness of those diplomatic negotiations between Germany and Great Britain resurfaced 11 years later. And they re-surfaced in a way that dominated world events for at least the subsequent 11 years as well.

Which of the three major stories of this week has the potential for such long-term consequences? Much of the answer lies in the nature of the resolution. Perhaps, the resolutions would be temporary fixes, only to re-surface in a short period, but enough to remove the crisis from the front pages. Or, perhaps the resolutions are of the muddle-through variety, allowing governments to contain the potential for escalation. Or perhaps, resolution is left untouched, as the crisis benefits specific, narrow self-interests of the parties involved? Rare indeed is the resolution that actually resolves a crisis.

Opposite the German diplomatic note story, on the far right hand side of the paper, 89 years ago, ran a larger headline: “Scopes Guilty, Fined $100.” Well, that certainly resolved the debate over evolution.

Thousands of Stories

Posted in Berkshires, History in our surroundings, Preservation on June 9, 2014

If private property is the foundation of our nation and its economy, there may be no better place to see it at ground level than in a registry of deeds, where records of real estate transactions are kept. The offices and rooms that house the documents offer a step back in history with their collections of oversized, dusty, heavy books and their card files of grantors and grantees (legalese for sellers and buyers) to ease tracing of ownership. Here one can find thousands of transactions which, taken together represent the legal underpinnings of our society. Separately, each deed tells a story and represents one of life’s milestones. The entries speak of hope and promise, of failure and tragedy of our forebears.

Admittedly, my sample size for registries is small – just two. But, if either of the Berkshire registries I’ve visited is any indication, there is no need for a time capsule. Crossing the threshold into these offices will suffice: they are housed in old buildings themselves with high ceilings, wooden floors and “scary” downstairs bathrooms, as one staff person told me. Hundreds of volumes are stacked either in floor-to-ceiling shelves or under stand-up counters upon which the books can be heaved and opened and studied. Each of the shelves has a roller at the edge to allow for easy access and maintenance of these volumes. The older tall shelving includes a bicycle-chain like contraption so they can be raised and lowered. Out of place are the occasional computer terminal and photo-copy machine that remind visitors that this is, after all, the 21st century.

The books themselves tell a story of innovation and change, but also of permanence. Now, of course, records are kept digitally as well as in books that are half the size of the pre-1970 variety – easily a foot and a half in length, a foot wide and three inches thick, representing 600-plus pages. At one time, the deeds were photocopied for these books, and even earlier they were individually typed with carbon paper. Prior to the 1920s, the deeds were each written out by hand, stirring images of Melville’s Bartleby facing a mountain of documents to carefully and neatly transcribe all day long. Over the almost two hundred years these oversized volumes have gone through periods of metal bindings and then transferred to hard leather and cardboard bindings rendering the documents they house safe from mishandling. Most are covered in a heavy, course fabric which shows the wear of use – the stains and spills and the rips.

The legal language remains surprisingly consistent over the past 100 plus years – warrants and grants, easements and quitclaims, and privileges and appurtenances. Likewise, a description of a property transferred that was surveyed in the 1800s carries over into this century, explaining that the property begins at a certain pipe adjacent or “thence easterly on the South line of land of said Bracewell heirs, 66 feet to a stake and stones.” Sometime the measurements are precise; other times they reflect bygone ways of measuring using rods and links, and still other times they are perilously vague and general.

Still, earlier social norms are hard to hide. There is a whole slew of deeds from the 1800s all the way up to the 1950s that announce in bold calligraphy at the top of the page: “Know all Men by these Presents” which by the sensibilities of 2014 sounds jarring in itself, but even more so when both the buyer and the seller are women. That is more common than one might imagine, given the prohibitions against voting and other social participation. For married couples back into the 1800s, it seems that wives insisted that the property be in both names. When only one name was given it was not unusual that it was the wife’s. If this was to protect against creditors going after debtors’ property, women stepped forward again to insist that any stupid financial decisions taken by the men in the family would not cause irredeemable harm.

It’s hard, though, not to see each transfer of ownership as a landmark event in each of these individuals’ lives. There are real estate tycoons who owned large tracts of multiple properties and sold off individual parcels; there is a surprising amount of stability in some neighborhoods, where families owned the house for decades, and then passed it on to their children. In others, there are sales every few years. The fluctuations in the economy are reflected in the housing prices so that it was not uncommon to see home prices higher in the early 1900s than in the 1930s. The saddest are the references to foreclosures or seizures by banks and courts and even sheriffs, more often than expected. This seems to take place just a few years after the purchase, leaving the impression that their ability to make house payments was limited even as they were buying the home.

Most people in these books are local, but I have seen sellers from Washington DC and Washington state, from Illinois and Idaho and Ohio and even one from London. There are a few investors, including one J. Walter Thompson from New York City, the advertising pioneer who came from Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The names also reflect the waves of immigrants that came to this part of Massachusetts, from Quebec and Ireland, Italy and Poland, and now Latin America. The Minnies and Leocadies and Annabelles have been replaced by Laurens and Jessicas and Christophers.

Each entry has a story, enough for a novel perhaps. Take but one entry, that of one deed from the Veterans Administration, to a man, presumably young, at the end of World War II. The VA had acquired the home following a foreclosure and turned it over, most likely to a veteran, recently married since the deed includes her maiden name. Both were from North Adams, so they could have met in high school on the eve of the war and kept up a correspondence through the war years. He had to have been young when they bought the house, since he passed away in 1987, forty years in the same house with his sweetheart. She hired a lawyer to place her house in a trust, to protect her largest asset, (again speculating) in the event her medical bills exceeded her ability to pay. This is the lived experience of veterans being rewarded for their service in a previous generation or the state of medical care in this century whose rising costs threaten a lifetime’s savings. Add to this story their children, the jobs, the neighbors and the vicissitudes of life in western Massachusetts with factory closings and 4th of July parades and winter storms. Where is Norman Rockwell?

And that’s just one couple, one of what must be hundreds of thousands of names tucked away in these books. Step back in time and find a story.